For most people, there are times when having a conversation can feel draining. Maybe we’re in a room full of people we don’t know very well, so we don’t know what to say to strike up a conversation, or maybe we’re having a tough day and really don’t feel like talking. But, for many people, starting a conversation just doesn’t come naturally.

For people diagnosed with autism, this is often the case. Taking turns in a conversation, picking up on social cues, sharing attention by attending to the same thing or event, and seeing things from another person’s perspective are important skills when conversing with others. They are skills that people diagnosed with autism often find challenging, but these skills can be learned.

Below are some tips for teaching initiating, maintaining, and ending a conversation.

TEACHING INITIATING A CONVERSATION

It’s hard to work on a goal if you’re not sure why it’s important, so in group therapy, my elementary school-aged students and I start by brainstorming reasons we should start conversations with people. Reasons include:

- Make a new friend

- Develop an existing friendship

- Learn new things by asking questions

- Share what you know by making a comment

- Make someone feel good by complimenting them and by showing interest in talking with them

- Offer assistance to someone in need

- Get needs met by asking for help

Then, we talk about the social rule of greeting a person before asking them a question or making a comment to start a conversation. We brainstorm different ways to greet someone. For example, “Hello, I’m Sylvia. What’s your name?” “Hi, how are you?” “Good to see you?” “Good morning,” and “Long time, no see.”

Next, we brainstorm and write down all sorts of things we could ask or comment about in general. Then, to make our practice more meaningful and enjoyable, we narrow the focus by creating a list of things the students in the group find interesting. Finally, it’s time to model and role-play initiating a conversation.

I have a student choose a person to talk to within the group. Once they’ve chosen, I ask, “Why did you choose this person?” This gives students practice thinking about their thought processes (metacognition) and the interests of others (Perspective-taking).

Sometimes students may say, “I don’t know.” If I continue to press, I may get a sigh of frustration. If this happens, I take a step back and provide verbal cues to help them. For example, I may say, “Hey, you’re the same age?” “She loves to play video games, too,” or “You both like to swim.” Then, we refer back to the list of interests we created earlier in the session to ask a question or make a comment to initiate the conversation.

Check out this Boom™Cards deck for practice initiating a conversation

TEACHING MAINTAINING A CONVERSATION

After we’ve practiced for several sessions and students can initiate a conversation with minimal verbal and/or written cues, we begin focusing on how to keep the conversation going. Before the students and I jump right into taking turns in a conversation, we lay the foundation for good communication by brainstorming and writing down what we can do with our bodies and words to show someone that we’re listening and are interested in what they have to say. These behaviors include:

- Maintain appropriate eye contact

- Face toward the person speaking

- Make sure facial expressions fit the conversation

- Maintain a distance that is not too far or too close to the person we’re talking to

- Stay on topic

- Give equal time for talking and listening

We start by setting a goal of two conversational turns per person. We use a ball to keep track of the number of times a student has taken a turn. It looks like this; after a student has asked a question or commented, they throw a ball to their conversational partner. After each person has held the ball twice, their turn is up. When students can question or comment twice with minimal verbal cues, we change the goal to three and then four turns per person in the conversation.

- Note: You can also write a period on one side of the ball and a question mark on the other side. Then, whichever one a student’s thumb is on when they catch the ball, that’s the way they’ll add to the conversation.

It’s a lot to remember and learn, so we take our time and work on it over several sessions. In the beginning, I’m the students’ conversation partner. I do this to help students learn to identify inappropriate behaviors by choosing one and modeling it. I may laugh inappropriately, turn away, look around, interrupt, answer off-topic, and not let my partner speak. After the behavior, I have the students tell me what I could have done better. Then, I model the appropriate behavior to show them what a better way looks like.

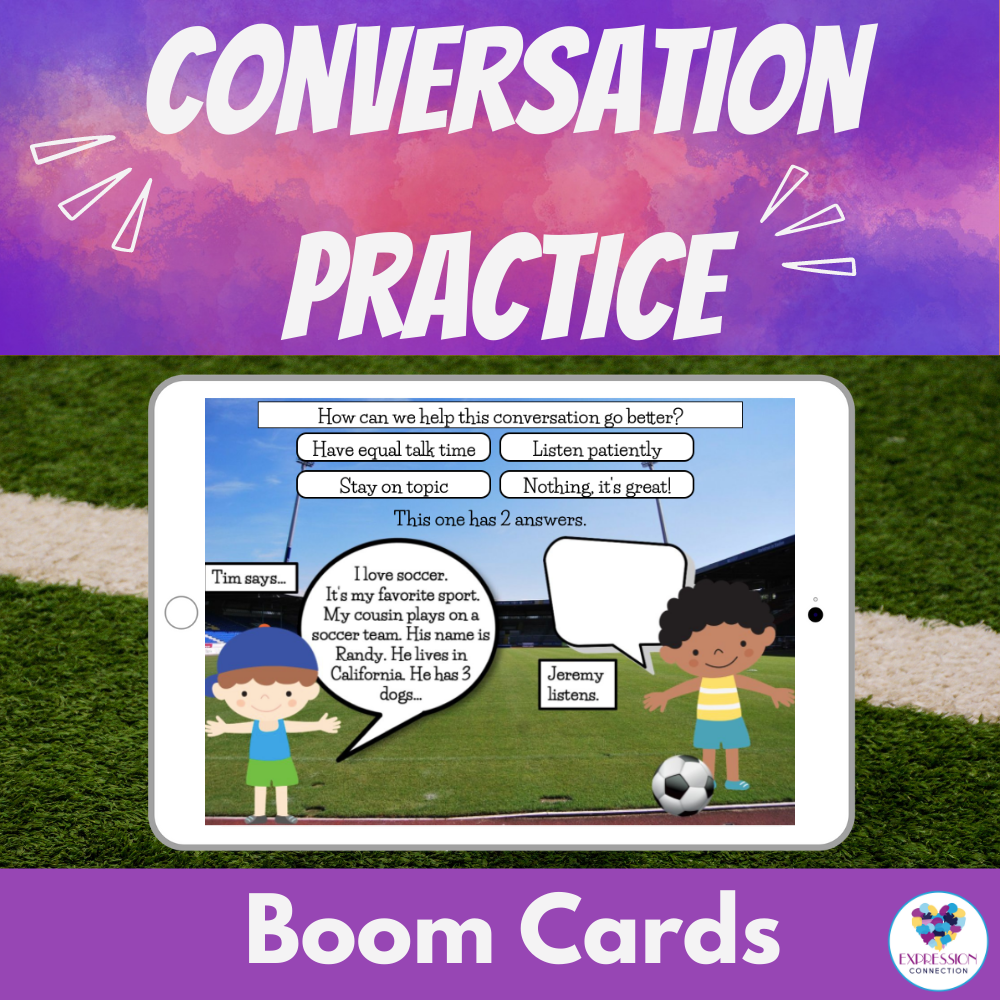

These Boom™ Cards are perfect for helping your student practice maintaining a conversation

TEACHING ENDING A CONVERSATION

Once students can take four turns in a conversation with minimal verbal prompts, we practice ending a conversation. There is often one of two reasons to end a conversation: a person has somewhere else to be, or either person is bored with the conversation. First, we brainstorm and write signals that show when to end the conversation. Some signals include:

- Running out of things to say and stop commenting and asking questions

- Beginning to look around

- Picking things up to leave

- Yawning

- Begin repeating yourselves

- Feeling the need for a break

- Feeling bored

Next, we talk about ways to politely end a conversation. The ways include:

- Give a good reason for leaving, “I have to get ready for baseball practice. It was nice to see you.”

- Politely excuse yourself. “It’s time for me to get going. Have a good day.”

- Talk about getting together in the future. “I’ll text/call you so we can make plans to see that movie that just came out. See you later.”

- Mention something about the conversation or time you spent together before you go. “The vacation you’re going on sounds like a blast. I hope you have a great time.”

In group therapy, we start by identifying how a conversation has ended. I will write down several scenarios on pieces of paper, fold them and have each student pick one. Then, each student reads it aloud and tells which of the four ways was used.

Once students can identify with minimal verbal cues, we do the same thing again, but on the pieces of paper, are ways to end a conversation. When students can role-play all of the different endings discussed with minimal cues, we incorporate ending a conversation into initiating and maintaining one.

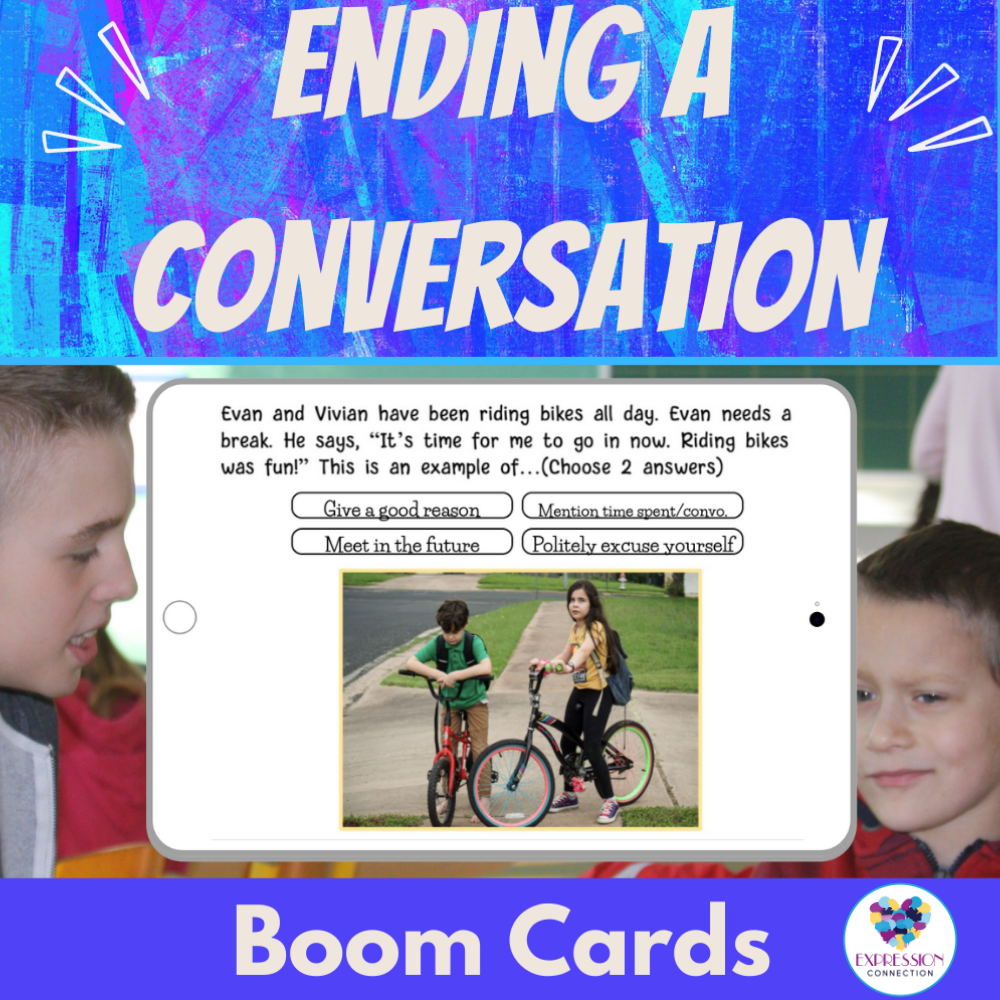

These Boom™Cards are great for practicing how to end a conversation

Thank you for this inspiring blog. The concrete suggestions and examples of ways to practice conversation skills are really helpful!